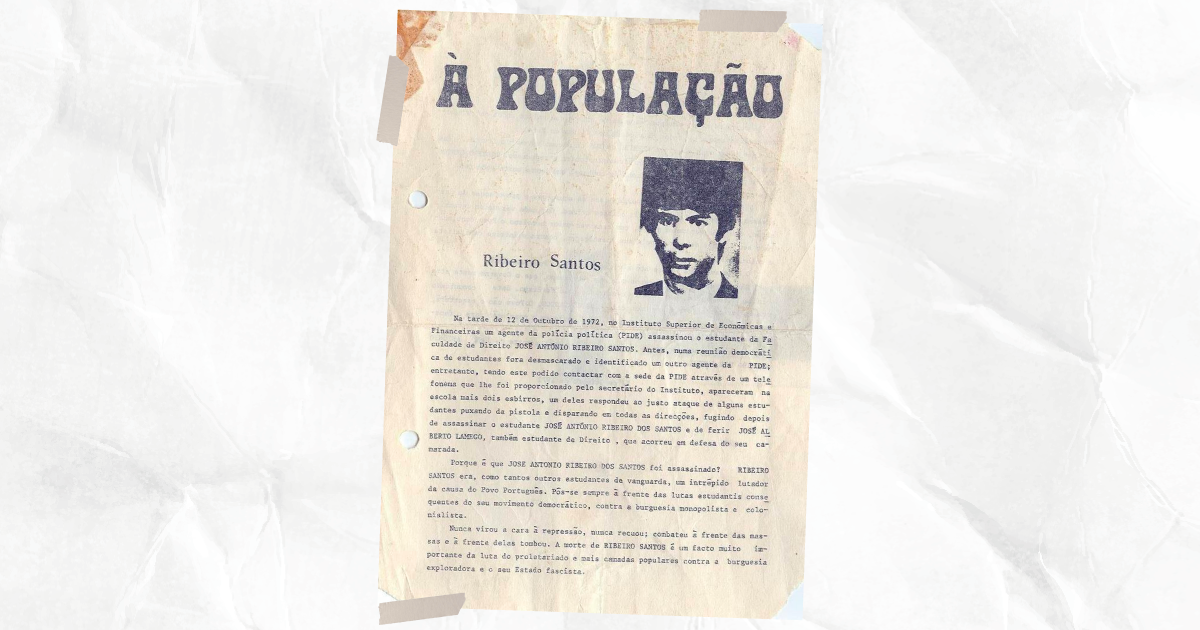

October 12, 2022 will mark the 50th anniversary of the assassination by the PIDE, here at the ISEG, of student José António Ribeiro Santos.

A session will mark the moment of violence and barbarity experienced in 1972 but which was also a relevant moment in the struggle for freedom and democracy at the ISEG, at the University, and in Portuguese society.

Commemorative Session

Oct 12, 3:30pm-4:00pm

Testimonials

October 12, 1972

Testimonial of António Garcia Pereira (taken from the interview to blog mitouverdade.blogs.sapo.pt on 16/03/2011) Professor at ISEG and law student, October 1972.

The assassination of Ribeiro Santos, was one of the most remarkable, it took place on October 12, 1972, in what is today my University - "Económicas" - now ISEG.

The student movement was going through a period of great repression, the "gorillas" were placed in the universities and dozens of students were arrested and tortured by the PIDE (only for fighting against the colonial war and for Freedom and Democracy). A meeting was called (as we called it) to discuss precisely the repression against the associative movement, in an amphitheater (which no longer exists today, but which later became known as Ribeiro Santos) and when the meeting was starting, we realized that there was an individual there who, in his anti-pide outburst, raised some doubts. Anyway, he was questioned, he said he was from Agronomy. There were Agronomy colleagues there and they asked him 2 or 3 questions about which subjects he had and which teachers he had and we quickly saw that this was a lie and realized that he was a "snitch" and that he was there to spy on the meeting.

At that point, he was restrained and a bag was put over his head (so he couldn't identify the people who were talking). We were discussing what to do with that individual and some time later, not long after, they entered the amphitheater, brought by (amazingly) both the secretary of the institute and two members of the student council's board of directors who, as it turned out, had their guns ready to fire.)

When they entered the amphitheater, this immediately sparked a huge revolt by most of the students. We threw ourselves at them, Ribeiro Santos, as always, was in the first line of combat, one of them was immediately subdued. When we were about to subdue the second one, those associative leaders, who on the justification of knowing if that individual was PIDE or not, went to call PIDE to say if the guy was or not. They started saying "Calm down, calm down!" and a split second of hesitation was created that gave the PIDE time to put on their jacket, shave a pistol, point it at Ribeiro Santos' chest and shoot him twice. At that time José Lamego (who was another law student) threw himself at him and grabbed his hand...The PIDE kept shooting in all directions and miraculously didn't hit anyone, but in the last shot the PIDE managed to turn the gun downward and hit one of Lamego's legs that with the impact of the bullet weakened and fainted a little. When Lamego fell he pointed the gun at him and squeezed the trigger and we heard the barrel of the gun hitting dry. He only didn't shoot because he didn't have any more bullets, otherwise he would have killed Lamego too.

This crime of Fascism, but also the huge day of struggle that followed, showed on the one hand what the regime was and its murderous nature, persecuting those who fought for freedom and democracy, with hired killers, as were the PIDE individuals, but it also showed that there was a people willing to fight, and in fact who walked the streets in the following days (he was assassinated on Thursday and the funeral was on Saturday), distributing communiqués, mobilizing the population to be present at the funeral (which was in fact a memorable day of struggle). One clearly got the feeling that that was the beginning of the end of the regime.

Also in the Year 1972

Testimony of Júlio Mota, student at ISCEF (now ISEG) in May 1972.

"Today I went to the dentist once again. All this because I carry a problem in my jaws that comes since an afternoon in May 1972. One of my jaws was fractured and one of the condyles has never been well since that painful afternoon at the ISEG.

I was asked to write a text this afternoon about my time at ISEG where I would also write about that other afternoon in 1972. The answer was ready: maybe, but with no commitment.

Here I am trying to satisfy that commitment, trying to remember that spring afternoon, almost 50 years later. It's a look back already a bit blurry, a lot of time has passed, a lot of water has flowed under the bridges and our lenses already worn out by time, age, have lost the polish that gives precision to our vision.

So I will speak in strokes about a time, about a country, about a school, about an afternoon in May.

- Four years had passed since May 1968, and the effects in Portugal were visible, fed by a war that was creating more and more victims, more and more people in despair about their future, especially the children of the small and middle bourgeoisie that would have military service ahead of them. It was 72 and we had a country segmented into: deep Portugal, the rural areas, living ideologically the regime's truth, and, economically, being victim of low relative agricultural prices, which we called internal unequal exchange.

- a working class generically mismatched between the in-itself as class and the for-itself as class behavior, living on low nominal wages and benefiting from the agricultural policy of low prices. Added to this was the introduction in Portugal of what we would later call make-up, industrial assembly basins, placed on the outskirts of Lisbon, using mainly culturally undifferentiated workers. In this period and in this industrial segment the pressure of the multinationals on the government demanding the devaluation of the escudo was enormous. The greed of these companies had no limits: it was not enough that people were paid low nominal wages, they had to make them even lower in foreign currency. They didn't hesitate to leave the country after the 25th of April, leaving thousands of women in the streets, without jobs, without anything, and with the roots of their origins already lost. Deduce the rest...

- a segment of workers that could be labeled as "labor" aristocracy and politically aggressive: Bank workers, Lisnave, Setenave, Siderurgia.

- A not very dynamic service sector and low value-added jobs. There was no easy outlet in the labor market for new graduates.

- a university youth who were facing going off to the colonial war.

We were a country, from every point of view, gagged, silenced. And this was felt in the student movements, from Técnico, Letras, Económicas, Faculdade de Ciências, and other faculties. Marcelo Caetano's government was heterogeneous, vacillating between the representative forces of Salazarism and the forces linked to the idea of the Marcelist Spring. Two examples, Veiga Simão for the latter, Gonçalves Rapazote for the former.

It was necessary to eliminate Veiga Simão and, for that, it was necessary to create chaos in the Universities. His compromise with the creation of the "gorillas" was not enough. It was necessary to give more to the right, which Veiga Simão would not give. An uprising by economics students was invented and it was necessary to respond with riot police. Personally I was, like hundreds of my colleagues, in classes. I was in Agricultural Economics with Professor Joaquim Lourenço, later a PSD politician and, by the way, my personal friend. As a student, I was on the right day, in the right place and at the right time fulfilling my student mission: to be in class. Suddenly it is known that riot police are raiding Economicas. Some students ran away, went home, others, like me, went to where the riot police were. There was already Francisco Pereira de Moura. Facing the police, I was in the front line, very close to Francisco Pereira de Moura.

This teacher tries to talk the police out of it, explaining that there was no movement of students. In vain, one hears the order for the police to advance. I still remember seeing a policeman with his truncheon wanting to shoot from high to low against Francisco Pereira de Moura's "bald head" and a shout from the commando: "not that one". The blow was narrowly avoided! The police advance and the students retreat. We escape into the building. We advance lost in the corridors. Some, like me, head for the so-called room 32, now the teachers' room. I try to escape through the window opposite the door. There is a three-leveled staircase-like hall that is accessed through the window opposite the door into the room. On the other side of the hall is the roof of the national broadcasting station.

I hesitate between jumping to the first level of the lobby or to the roof of the station. I am afraid that the roof of the broadcasting station will give way with my jump, and I opt for the descent down the lobby, to take refuge on one of the floors below. A split-second decision. The shoes, mittens, had gone to life and the socks were not pure Egyptian cotton. I jump, fall and try to get up to jump to the floor below, and when I get up, I slip: the socks were made of a lot of nylon and little or no cotton. The end of that landing was tile, the tile broke with my weight as I slipped, and I broke as I fell to the second floor of the lobby, falling uncoordinated on top of a pile of stones. I am immobilized. Someone then picks me up. I am taken to the São Bento clinic opposite the entrance gate on Miguel Lupi. I am said to have fallen into a coma. I am then interrogated by the PIDE, I don't know where, I only remember that it was in a dimly lit office. There was no answer from me, blood was flowing from my mouth. Later my face hurt. I was sent to St. Joseph's Hospital. From here I remember two moments:

Moment 1. On a stretcher I felt the blood draining out of my mouth. I am a son of that deep Portugal, of poor peasants, very poor, I am a son of that deep Portugal enslaved by corporatism and massacred by internal unequal exchange, the invisible exploitation, which I learned in the third year with Arghiri Emmanuel and his Unequal Exchange. I had one worry: I am going to die, my father is already dead, what will become of my mother, widow, illiterate and landless peasant. From that stretcher, that corridor, I still remember today and I would say, like Margarite Yourcenar, my body was there like a river, a river of tears.

I am operated on and placed in a ward with 6-8 beds and, if memory serves me correctly, it was an incredibly empty ward, as if there were not too many patients in Portugal. I was literally forbidden to speak, with my jaws fixed and tightly clamped by special metal wires. I could only drink liquids through a straw and through the space left by a tooth that had also come out in the fall. I listen to what I am told, I answer in little notepad notes.

Two days later my mother arrives, a wounded image of the aforementioned deep Portugal. Dressed in black as any widow of that stratum should be, without a tear in her eye, she asks me how I am. I need an "interpreter", in this case my then girlfriend and then my wife until tomorrow, which I hope is still far away. My mother couldn't read or write, although no one could fool her in her math. Algorithms! It is my girlfriend who reads my answers to her.

The old woman in front of me typifies this deep Portugal and feels hurt by what she doesn't understand. She doesn't understand why her son is there, in a hospital bed when, from her point of view, and mine too, he wouldn't have hurt anyone. She knows I like honey cornbread, but the son of a poor peasant didn't like sweets and ate them with cordevil olives, olives that are more acidic than the other kinds. Tell me what you eat, how you eat, and I will tell you where you come from, Marx is said to have said in Grundrissen. My mother tells me that she brought a basket of cornbread, cornbread that she couldn't eat, I gave it to her. And she tells me a story:

When she learned that she was in the hospital, she goes to her grocery store and buys flour and sugar. She had the rest of the products she needed. In the store she met a cousin who had a son, a primary school teacher in Lisbon. He was suffering from epilepsy, said to be very bad. I took care of everything regarding doctors, treatments, with special recognition to Professor José Luís Simões da Fonseca who I became friends with and who treated him. His mother was grateful to me for that. But... the fascist ideology, the official truth, came to him and he forgot everything else. He turns to my mother and insults her by telling her that she should be ashamed of herself for having a communist son. And he added: your son should be in jail. The ideology of fascism in all its fullness: whoever is not for us is against us and whoever is against us is a communist and a communist should be arrested. This is what was done with the militants that belonged to the Communist Party structures. The full-blown demonization rooted in many people in deep Portugal was there clearly in evidence, in this painfully told story, which mirrors what the fascist Beast was...

Moment 2. I am discharged, the metal wires that were fixing my jaws are removed, and I go back home, to Gomes Freire Street. A short time later Vítor Nogueira calls me saying that a colleague of ours is stuck in the cafeteria, he can't go home because the PIDE is waiting for him outside his house and he has nowhere to go. The pressure of the PIDE on the students continued despite the events that had occurred. In fact, following the occupation by the police, I learned later on, from a brother-in-law of Veiga Simão - who worked in my hometown in topographical surveys - that there was a Council of Ministers where Veiga Simão got into a fight with Gonçalves Rapazote. They had to be separated by other members of the Council! There was nothing in the newspapers. But Vítor's phone call indicated that the PIDE was not easing its pressure on the student movement. In this case, it was Chico Cal. Vítor Nogueira asks if he can go to my house. I tell him it's not the most appropriate place but, between the certainty of being arrested and the possibility of not being arrested, there was no choice, he had to come then. But my house was not the right place, in that context.

I got him a country house rented by a couple of friends of mine, on the Costa da Caparica line, near Praia da Riviera, I believe that's the name, between Praia da Rainha and Praia do Rei. I know today that these friends have already died and from here I salute their memory vigorously. With this loan of the house and the risks associated with it, they thus entered the chain of solidarity that would protect Chico Cal.

Chico Cal went underground this way, without the means to do so. My girlfriend was in charge of bringing him food two or three times a week. She bought the food at the military "supermarket" on Rua Artilharia 1 (her father was a Navy officer) and took it to him. In this mission, every time I went to see Chico, I was guaranteed to miss classes at the Science College. By the third week she warned me that it could be dangerous to go to Chico alone. It was June. The bus on the way from Costa to Fonte da Telha was always practically empty. Halfway through the journey it would get out and it would be a young woman with some bags who would take a path through the countryside! It was too visible, not to say strange, for a girl alone to go into the woods. My girlfriend was right in what she said, it was better to reduce the risk, we thought.

Faced with what she tells me I feel that I have no one to turn to because I could endanger both Chico's life and the life of someone I could turn to in our midst for help, so I decide to go myself. I turn to a friend of Técnico, a student who is far away from the academic struggles, and ask him to take me there by car. He drops me off in the same place where my girlfriend was staying, he drives me to Fonte da Telha, goes around it a few times and then turns around to pick me up and bring me back to Lisbon.

The very first time, and the only time, I get to Chico Cal and he tells me: the GNR came by here and I told him what you told me: that I am in exam season and that I came here to study as a concession from Mr. Campos' tenant, the owner of the house. I got scared. I had read in the newspapers that a few days before a high ranking member of the underground PCP had been caught in those parts. And as a reaction I told him: you did well and I'll tell him about the case of the PCP cadre. We have to leave, I added. Leave the food here. And we went back to my house. Those were times of solidarity. One risked a lot for a colleague, a friend or acquaintance, for the idea of freedom, regardless of the ideas that this colleague represented. This was the case. I had nothing to do with Chico's Maoist political line. However, it was necessary to cover that situation of the GNR passing through the backyard of the house. A day or two later, the study group that I was part of and my girlfriend went there to study for a whole day on Saturday, with lunch and everything: it was necessary to eat the food that had been brought. Some of the group knew the reason why we were going there, others didn't. It was better not to know, in case there was a scolding. I stayed until Sunday. One or another of my colleagues from Saturday came back to keep me company, we were left as a rearguard for an eventual passage of the GNR.

I then put Chico in the house of a friend of mine, on Rua Dr. Mascarenhas de Melo. This friend, a radio employee and writer, had a housekeeper. She introduced Chico to her as her translator. Some days later the maid calls my friend, who was at work, and tells her: look, your translator doesn't translate anything. My friend is frightened and explains to her that he needs to read a lot first, but her fear remains in the air. Days later a serious incident: Chico was eating in the house. That could be. And the building's janitor comes up to my friend and laughingly asks her what changes had taken place in the house to make there be a lot more garbage. She tells me about it and my reaction was the same: you have to leave. And she left for another house, fixed up in the same way.

It was a time of fascism, a time of surveillance, a time of Orwell's 1984 but with rudimentary means. A janitor on one street could report on everything that went on in that street, using a classic weapon: gossip with other janitors. And the PIDE used that. Knowing this reality, which I didn't know about until then, I became much more respectful for the multiple anonymous members of the PCP who lived years and years underground, where fear of prison or death was around every corner. But they had support structures, the student left did not.

In this escape from house to house, Chico Cal went through yet another house, in a clandestine arranged by a colleague of his, me, with no experience of political organization, until he fled abroad. He came back after the 25th of April, and came back well. We met. After this encounter I never saw him again. Curiously, the same situation occurred with a colleague from the Faculty of Science, now a local PSD leader somewhere, and was repeated almost like carbon paper.

I recount this detail because it shows us the students' organizational incapacity as opposition to the system. This opposition in a structured way was mostly on the other side, in the PCP, whether you like it or not. Why then this police pressure on the student movement? The answer seems simple to me: the political system was weakened and could not withstand major student upheavals like the crisis of '62 or the Coimbra crisis of '69. It would fall in '72 if either of these two crises were repeated in intensity, given its political fragility. The Portuguese extreme right wing thought it was necessary not to run any risks of this type, and it was necessary to block all paths that could lead to this type of crisis. This imposed enormous pressure on the PIDE over the student leaders.

Complicating this work of the PIDE was the fact that the student movement was relatively fragmented along so-called "political lines," a fragmentation that would in principle work in favor of the institutions of repression, which would confirm the expression divide and rule. But it didn't work that way, it worked the other way around. Given this fragmentation, acts of student unrest multiplied, produced by the student movement associated to each of the tendencies, even with lightning disturbances in the street and without some of them even being announced. The PIDE, disturbed, began to multiply police reinforcements in the detection and consequent repression of its leaders. It is still within this framework that the murder of student Ribeiro dos Santos took place in October of the same year. Even today I am moved when I recall the images of his funeral, even today I remember the sea of people at his farewell in the Santos square.

The work of detection and persecution increased in intensity and it was confirmed that no axe could cut the root of thought or neutralize its capacity to spread and influence. And this root had to be blocked by all possible means, otherwise it could spread and strengthen the political opposition forces that existed outside the Universities, and dangerous centers of political instability would be created as a result. It was on this repression and neutralization that Gonçalves Rapazote and the extreme right were betting. We must not forget that in each student movement on the street or in the universities, it was the flame of freedom that was wielded and spread, which was dangerous for the system. In power or close to it, and against this extreme right-wing political line, we should mention the names of Galvão Telles and Adriano Moreira before 72, and afterwards those of Veiga Simão, Miller Guerra, Rogério Martins, João Cravinho, and many other moderates on the left. To all these moderates, Portuguese society owes a lot, let's not ignore it.

From this multiple movement came another danger. What this student left showed, in general terms, was its existential restlessness, the revolt had more to do with the denial of the daily life that was being imposed on them and, let's not forget, with the war in between, than with a solid political vision of the future. Some had it, I met several, both in Economics and in other faculties, but they were not enough to consider themselves as a political opposition to the system. For that, more was needed, much more. And that much more came with the reality of the 25th of April.

To conclude this text about events of fifty years ago, I think that the 25th of April confirmed that the Portuguese extreme right was right, from its point of view, in considering dangerous and in wanting to repress and neutralize the various left-wing student movements but for reasons it could never have imagined: the student cadres created and made aware in this climate of revolt were an important part in the realization of the military coup of the 25th of April and much more important still were in its transformation of this military coup into Popular Revolution, given the characteristics of deep Portugal mentioned above, but that's a whole other story."